Bidding for keyword ads in online auctions has become popular in modern political campaigning, and is seen by many as a major tactic to increase the number of supporters.

MICHAEL BLOOMBERG IS SPENDING MILLIONS ON GOOGLE AD AUCTIONS

If you have recently googled “impeachment” in the US, you would see Michael Bloomberg’s presidential campaign ad as the top result1. Bloomberg has been spending immense amounts of money acquiring the spots for the top keywords in Google Ads, to promote his candidacy in the US presidential race. This is part of a much larger trend. Bidding for keyword ads in online auctions has become popular in modern political campaigning, and is seen by many as a major tactic to increase the number of supporters.

Figure 1: Michael Bloomberg’s Google Ad for impeachment

Combining online search with advertising is a lucrative market that allows the advertiser to directly target the audience they are interested in. Although the bidding for keywords in a Google Ad auction might seem like an easy task, there are complex decisions that need to be weighed up by the presidential candidates. Using game theory to understand the auction mechanism, and its subtleties, is key in determining the optimal bidding strategy.

GOOGLE ADS USES A GENERALISED SECOND-PRICE AUCTION TO SELL ADS FOR KEYWORDS

Google Ads is probably one of the most widely used ways of online advertising these days, offering a unique way to sell advertising online to a targeted audience.

In general, online auctions are based on a pay-per-click model. In this scenario, it means that Michael Bloomberg would only pay for the advertisement if a user actually clicks on the link. Such a model is very successful, as it represents the strong intent of the user, who not only searched for the term, but also read the advertisement and visited the web page.

Microtargeting, as it is known, is not the only benefit of search ads. Displaying advertisements alongside the normal search can be argued to result in a cognitive bias leading to greater credibility. As a result, the amount that advertisers are willing to pay for such users tends to be very high.

Sometimes, the cost can be of a different dimension. Addiction clinics, mortgage institutions and law firms, for example, are willing to spend quite the buck on pay-per-click. Placing the word “insurance” on Google’s prime real estate spot would set the advertiser back $55 per click2. As a result, advertisers would want to gain an expected value at least equivalent to the amount of the bid.

To sell the advertising spots for keywords, Google uses a generalised second-price auction (GSP) mechanism. Let’s consider a simple example, where there are two advertising slots for a given search word. If there are three bidders, the top two winning bidders will get a chance to display their ad. The price that each winning bidder has to pay, however, is not equivalent to their own bid, but is the value of the bid that the individual below them has placed. That is, the highest bidder will pay the amount of the second highest bidder plus a cent.

DETERMINING THE BIDDING PRICE CAN BE A TRICKY BUSINESS

In general, when advertisers place ads with Google and determine their bids, they would want to consider the revenue-per-click. The expected amount of revenue the advertiser receives from a user clicking on the ad is a key figure to determine the maximum bidding price. The valuation for the slots should be the multiplication of the revenue-per-click by the click-through rates (the number of clicks per hour that the ad attracts). This would in turn dictate the market-clearing prices for the lots.

In the presidential election case, the valuations are not very clear as there are no revenues associated with individual users. The valuations should be linked to associated increase in likelihood to vote for the candidate. Valuations may also be determined by the candidates’ willingness to pay for ads that also harm other candidates, as in the “impeachment” keyword example.

Different candidates may have different valuations that would shift with the level of overall support a candidate has. It may be the case that with increasing the number of voters for the candidate, their valuation for the slots will decrease as the winning probability can be near certain. This would make determining the advertiser valuations from keywords tricky from a budget perspective.

TRUTHFUL BIDDING IS NOT A DOMINANT STRATEGY IN GSP

To encourage bidders to reveal their true valuations and make it a dominant strategy is a key issue facing the search engines. In the currently adopted version of the generalised second-price auction for online search ads, the truth-telling mechanism may not be an equilibrium.

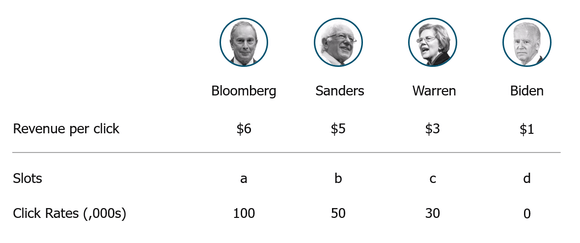

Figure 2: Expected revenues per click for candidates and click-through rates for three ad slots

Imagine a situation where Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and Joe Biden – the other top three candidates from the Democratic party – are interested in the same keyword as Michael Bloomberg. They may then be competing for “impeachment” together with Bloomberg. Knowing that Bloomberg has the deepest pockets, all three understand that it would not be possible to outbid him in an auction and they chose to compete for the second and third slots – b and c – instead. As the campaign budgets are publicly available, Sanders may reckon that Biden cannot afford to compete for the third place slot with him, and would try to place the minimum bet to outbid him.

In the “truthful” scenario, Sanders would bid $5 and Warren $3. Sanders would then win slot b with a payoff of $5*50 – $3*50 = $100.

In the “lying” scenario, Sanders would lie about his valuation and bid $2 instead. Sanders would then win slot c with a payoff of $5*30 – $1*30 = $120.

Sanders’ payoff from lying is greater than the payoff from being truthful, implying that it is in his best interest to reduce his bid below the estimated revenue-per-click. In the “lying” scenario, Warren would then get the second slot, Sanders third, and Biden would lose out on the ad spot for this particular keyword.

In reality, the Google Ads auction takes place on a continuous basis, meaning the candidates may attempt to vary their bids and investigate the auction results. In our example, Bloomberg, Sanders and Warren would likely be able to find an equilibrium solution allowing them to lower their bids below revenue-per-click while increasing the payoff from advertising.

The presented example is of course a simplified version of the real-world case. Google Ads also employs other factors that form the bidding prices. One factor is the quality score of the web page advertised3. This is used for reputation purposes to improve the relevance of the ad and to not discourage the search users from clicking on future advertisements.

GAME THEORY CAN HELP OPTIMISE BIDDER STRATEGIES IN ONLINE AUCTIONS

In the political environment, understanding valuations and selecting strategies for search auctions can be difficult and needs to be optimised on a case-by-case basis. The above example has shown that even in the second-price auction there are situations where truthful bidding is not the one leading to the greatest payoffs. Real life is more complex, with the variety of factors to be considered going beyond estimating bidder valuations. It may be the case that there are deals between advertisers to avoid bidding for the same keywords, or there might be strong externalities from placing online ads, implying that private benefits to one candidate’s advertisement is different from wider social benefits. The strategies are dynamic and need to be adjusted in the complex environments with other factors at play.

SOURCES:

1) Michael Bloomberg Ads Are Dominating the Internet – slate.com

2) How Does Google Make Its Money: The 20 Most Expensive Keywords in Google Ads – wordstream.com

3) Google Support guide on bidding on keywords in the Google Ads auction – google.com

Title image by Christian Wiediger on Unsplash