How the National Hockey League (NHL) managed to create a level playing field for their teams

My interest in German club football has very much dried up over the last few years. Even as a Bayern Munich fan since childhood, I gradually got bored by the Bundesliga where nowadays the only questions at the start of each season seem to be ‘who will be this year’s main challenger for second place?’ along with ‘by how many points will they be trailing Bayern Munich?’. In parallel, I have become an avid follower of the NHL, i.e. the North American ‘super league’ for ice hockey. Not only has this league seen the emergence of its greatest super star since the 1990s in Connor McDavid, it has also managed to demonstrate that a professional sports league can actively create the environment for balanced competition among its teams.

Competition instead of dynasties

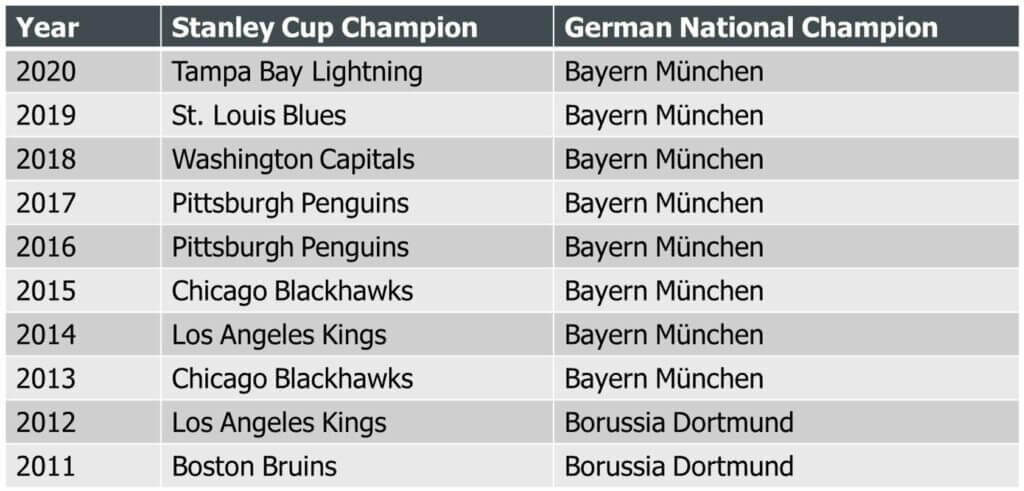

A look at the past winners of these two competitions tells us that since 2010, there have been seven different Stanley Cup Champions in the NHL, whereas the Bundesliga’s equivalent has only been hoisted by Bayern Munich and Borussia Dortmund in the same time period, with Bayern winning 8 out of the 10 times.

Champions overview of the NHL and Bundesliga in the last 10 years

The perception that almost any team could win the Stanley Cup has not always surrounded the NHL. In fact during the 1970s and 1980s, the league was similar to the Bundesliga right now and characterised by so-called dynasties – where teams like the Montreal Canadians or the New York Islanders both managed to win four Championships in a row. However, the league has over time implemented distinctive instruments, all aimed at improving the competitive environment of the league and ensuring a level playing field for all teams:

1. Hard salary cap

The dynasties of the 1970s and 1980s could be installed by the mentioned teams because their revenues were significantly higher than those of other teams in the league. With their increased financial firepower, these ‘large market teams’ were able to pay much higher salaries than the ‘small market teams’ and consequently could assemble the best players the sport had to offer.

To address this, the league introduced a salary cap, which limits the overall amount a team can spend on player salaries in each season. This overall amount is the same for every team in the league and is directly tied to the overall revenue generated by the league, e.g. ticket sales, merchandise and TV revenue. This ensures that the cap is linked to the attraction the league creates and avoids that teams will accrue excessive debts because their revenues are not covering player salaries.

The NHL has implemented the cap as a hard cap. This means that even teams that would have the financial leeway to exceed the maximum amount are prohibited from doing so. In contrast, teams in the NBA for example may pay a ‘luxury tax’ in case they want to exceed the maximum amount.

2. NHL entry draft

Even with the hard salary cap in place, the large-market teams still could use their financial advantage to lure the best talents at a young age. This is where the NHL entry draft comes into play.

This annual event is the NHL’s approach to regulating teams’ access to future prospects. Prior to the event, all eligible players (global talents who have reached the age of 18) are ranked by a group of independent scouting organisations. The 31 NHL teams are then entered into a selection order that is determined by several different factors, but designed to favour the weakest teams who need fresh talent the most. The basic order is determined as follows (simplified):

- The teams that failed to qualify for the playoffs.

- The teams that made the playoffs but did not finish top of their division.

- The teams that finished top of their divisions

- The team that lost in the Stanley Cup Finals.

- The team that won the Stanley Cup.

The individual rank of each team within these groups is determined by the points total of the previous season (a lower point total receives the better rank) with one exception: given that there are usually just a handful of future elite players in each draft year, the draft rules need to avoid incentives for ‘bottom-dwelling behaviour’, meaning that a team might choose to perform poorly for several seasons in order to acquire the best talents available.

The selection order for the first three picks is therefore not determined by the points total of the previous season, but rather by the draft lottery. The team with the worst record is assigned an 18.5% probability of winning the lottery, while the team with the 15th-worst record (i.e. the best team in group 1) is assigned a 1% probability. For example, the 2015 entry draft determined that aforementioned future superstar Connor McDavid (ranked number 1 by all scouts) was picked by the Edmonton Oilers who had posted the third worst record in the previous season but still managed to win the draft lottery.

Once the draft order has been determined, each entry draft consists of seven rounds of all teams selecting players. Each team can either follow the recommendation of the scouts or choose freely among the remaining player pool.

3. Entry level contracts, free agency and trade system

Another area for potential exploits, especially for large-market teams, is to acquire players by offering lump sum payments or other concessions to either the smaller teams or players directly. This is where the third regulation instrument comes into the equation.

Once a player has been acquired by a team via the entry draft, he signs an Entry Level Contract (ELC) with that team. This is (usually) a three-year agreement with conditions dictated by the NHL, including a salary at or slightly above the league minimum. Once this ELC expires, the player is considered a restricted free agent, meaning that any contract offered to the player by another team can be matched by the existing team to retain the player. Additionally, offers can only be made to the player once negotiations with the existing team have been unsuccessful.

Given this ‘last call’ rule, other teams very seldomly opt to lure away players during this status of free agency. The first time a player can really be approached openly by other teams is as an unrestricted free agent – a status that is granted to players (whose contract has expired) at the age of 27 or after seven seasons in the NHL.

This ensures that teams have a relatively high planning security for their young talents and leaves trading of contracted players as the only means of acquiring players that are not unrestricted free agents.

Controversially to the common practice in European football, such trades cannot include any cash concessions for the trading partner. Instead, the only assets NHL teams may exchange are (contracted) players and/or future picks in upcoming entry drafts. For example, a team preparing for a Stanley Cup run may trade away a young player and a future first-round pick for a veteran player from another team that is currently rebuilding and focusing on acquiring talents for the future.

Championship decided by skills, not money

With this set of regulations, the NHL has created an environment where the winner of the league’s championship is decided much more by skilled team management (and of course performance on the ice) than by the financial firepower of its heterogenous members. However, the application of the system to European football would not only be impeded by European competition regulations, but also by the large number of different leagues and teams in the European market.

Ironically, the establishment of a European Super League, assembling the top clubs in a closed system, would therefore be a first step to bringing more balance to European football and breaking the monotony currently present (not only) in the German Bundesliga. It is more than doubtful though, that the advocates of the European Super League had the introduction of the above system very high on their priority list.